Half a world away from the opioid epidemic ravaging the United States, Australia is facing a crisis of its own, with skyrocketing rates of opioid prescriptions and related deaths.

The country has failed to heed the lessons of the U.S., and has been slow to respond to years of warnings from worried health experts. The crisis comes as drug companies—facing scrutiny for their aggressive marketing of opioids in America—have turned their focus abroad, working around marketing regulations to push the painkillers in other countries.

In dozens of interviews, doctors, researchers and Australians whose lives have been upended by opioids described a plight that now stretches from coast to coast. Australia’s death rate from opioids has more than doubled in just over a decade. And health experts worry that without urgent action, Australia is on track for an even steeper spike in deaths like those in America, where the epidemic has left 400,000 dead.

“It’s depressing at times to see how we, as practitioners, literally messed up our communities,” said Dr. Bastian Seidel, who warned that Australia’s opioid problem was a “national emergency” two years ago when he was president of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. “It’s our signature on the scripts.”

He sees Australia moving with willful ignorance toward a disaster.

“Unfortunately, in Australia, we’ve followed the bad example of the U.S.,” he says. “And now we have the same problem.”

Starting in 2000, Australia began approving and subsidizing certain opioids for use in chronic, non-cancer pain. Those approvals coincided with a spike in opioid consumption, which nearly quadrupled between 1990 and 2014, says Sydney University researcher Emily Karanges.

As opioid prescriptions rose, so did fatal overdoses. Opioid-related deaths jumped from 439 in 2006 to 1,119 in 2016—a rise of 2.2 to 4.7 deaths per 100,000 people, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

More than 3 million Australians – an eighth of the country’s population – are getting at least one opioid prescription a year.

In the U.S., drug companies such as OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma are facing more than 2,000 lawsuits accusing them of overstating the benefits of opioids and downplaying their addictiveness.

In Australia, pharmaceutical companies by law cannot directly advertise to consumers, but can market drugs to medical professionals. And they have done so, aggressively and effectively, by sponsoring swanky conferences, running doctors’ training seminars, funding research papers and meeting with physicians to push the drugs for chronic pain.

“If the relevant governing bodies had ensured that the way the product was being marketed to doctors especially was different, I don’t necessarily think we would see what we’re seeing now,” says Bee Mohamed, who until recently was the CEO of ScriptWise, a group devoted to reducing prescription drug deaths in Australia. “We’re trying to undo ten years of what marketing has unfortunately done.”

Mundipharma, the international arm of Purdue that Purdue’s owners have proposed selling to help pay for a settlement in the U.S., has received particular criticism for its marketing tactics in Australia. Mundipharma also runs “Pain Management Master Classes,” which have provided training to more than 5,000 doctors in Australia. The classes have been praised by some as helpful and condemned by others as a conflict of interest.

Mundipharma said the classes cover non-opioid treatment options and “strongly emphasize” that opioids are only appropriate after a comprehensive assessment. In a statement, it also said it strictly adheres to the code of conduct of the pharmaceutical industry’s regulator, Medicines Australia, and has always been transparent about the risks associated with opioids.

Like in the U.S., the problem has hit the country’s poorest areas the hardest. One region of Tasmania—Australia’s poorest state—has the highest number of government-subsidized opioid prescriptions in the nation: more than 110,000 for every 100,000 people.

In poor, rural areas, access to pain specialists can be logistically and financially difficult. Wait lists are long, and a few sessions with a physiotherapist can cost hundreds of dollars. Under the government-subsidized prescription benefit plan, a pack of opioids costs as little as AU$6.50 ($4.50.)

It’s a system that has made opioids the cheap and easy alternative for Australians, particularly the poor.

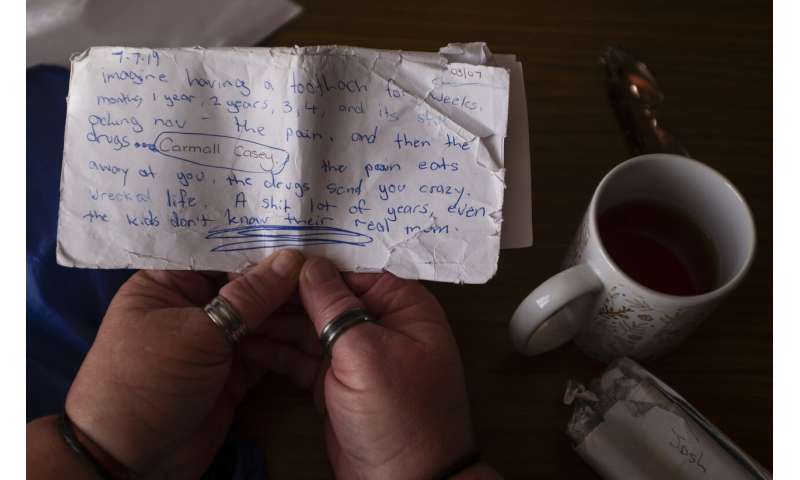

For years, Tasmanian Carmall Casey sought treatment for knee pain, only for doctors to send her away with prescriptions for opioids. When her pain returned, the doctors upped the dose. That led to a devastating addiction that took her years to overcome.

“I became an addict without knowing,” Casey says.

David Tonkin blames his son’s death from prescription opioids on a system that allowed him to see 24 doctors and get 23 different medications from 16 pharmacies—all in the space of six months. Between January and July 2014 alone, Matthew Tonkin got 27 prescriptions just for oxycodone.

Matthew’s doctors were largely oblivious to what he was doing because Australia has no national, real-time prescription tracking system.

Coroners nationwide have long urged officials to create such a system. But the idea has been mired in bureaucratic delays.

Australia’s government insists it is now taking the problem seriously. The opioid codeine, once available over the counter, was restricted to prescription-only in 2018. And last month, the country’s drug regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, announced tougher opioid regulations, including restricting the use of fentanyl patches to patients with cancer, in palliative care, or under “exceptional circumstances.”

“I can’t speak for the past,” says Greg Hunt, who became the federal Health Minister in 2017. “I can speak for my watch and my time where this has been one of my absolute priorities, which is why we’ve taken such strong steps. … My focus has been to make sure that we don’t have an American-style crisis.”

But for Sue Fisher, whose 21-year-old son Matthew died in 2010 of an overdose, it’s too little, too late. The crisis is here, along with what she calls a “crisis of ignorance.”

Source: Read Full Article