With electronic medical records creating an ideal source of data to inform quality care and new discovery, a key question emerges: How much say should patients have in how their data is used?

A new study led by Michigan Medicine researchers finds that even when patients understand the overall benefit to society, they still want to be able to give consent at least once before their de-identified data is used for research. The feeling was especially strong among racial and ethnic minorities.

“What we heard was a resounding sense that people want to be able to control their data,” says lead study author Reshma Jagsi, M.D., D.Phil., deputy chair of radiation oncology and director of the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine at the University of Michigan.

“Many patients indicated they fully intended to allow for their data to be used, but they wanted the respect of being told and having the chance to say no. Programs trying to facilitate use of data collected in routine patient care encounters for other purposes—even highly worthy ones like improving the quality of care and research— need to be mindful of transparency and clarity in the communication of their goals and activities so patients don’t feel violated when they find out how their data was used,” Jagsi says.

In 2015 the Institute of Medicine advocated for developing learning health care systems, in which science, informatics, incentives and culture align to create a cycle of continuous learning and improvement. Learning health care systems tap into de-identified patient data from electronic medical records of participating medical practices to inform quality improvement, innovation and best practices.

While previous research suggested patients had some unease with their data being used for research without their permission, these earlier studies often did not focus on making sure patients understood how this research could improve care or the importance of including all possible data to maximize benefit to the community.

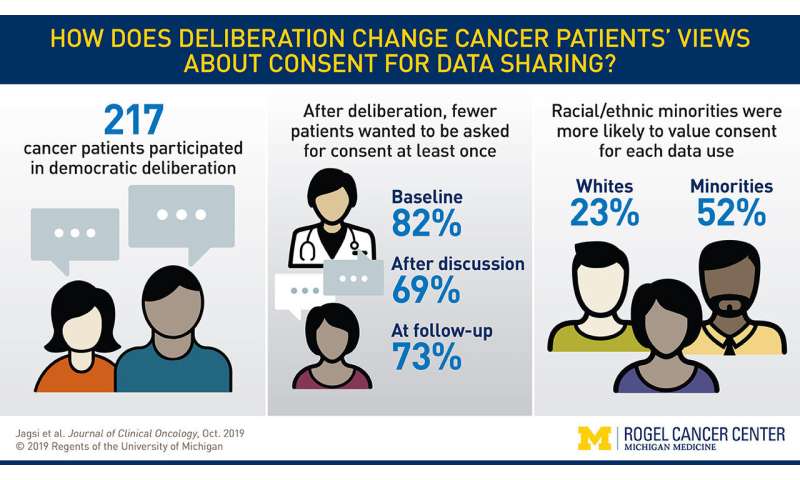

In this new study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, researchers used a novel approach called democratic deliberation. Participants were given information about why and how data is used, followed by facilitated small group discussions about the benefits and concerns. Participants were surveyed throughout the process to assess their attitudes toward use of de-identified patient data for research. Altogether, 217 cancer patients participated at four diverse sites in day-long democratic deliberation sessions.

The vast majority of participants—97% – thought it was important to conduct medical research using de-identified electronic health records. Support for academic medical centers or community hospitals seeking to improve quality was high, but fewer people were comfortable with insurance companies or drug companies using their data, as well as hospitals using their data for marketing purposes.

Initial surveys showed 84% of participants thought it was important for doctors to ask patients at least once whether their de-identified data could be used for future research. That number dropped to 66% after discussion. A month later, 75% wanted to give permission.

Race and ethnicity played a significant role. White participants were less likely than non-white participants to value consent. Half of the minority participants expressed wanting to give consent every time their medical records were used, compared to a quarter of white participants. Jagsi says this discrepancy likely reflects historical injustices experienced by minority populations in the context of clinical research. She emphasized that systems must be structured in ways that all patients feel respected so that they do provide access to their data—especially since minorities are often underrepresented in research.

Source: Read Full Article