Twinkling lights make a city view all the more beautiful at night, and may evoke feelings of romance and happiness. But what do those feelings look like inside the brain? Recently, researchers in Japan demonstrated that the power of light may also be harnessed to monitor release of the “happy hormone” oxytocin (OT), a peptide produced in the brain that is associated with feelings of happiness and love.

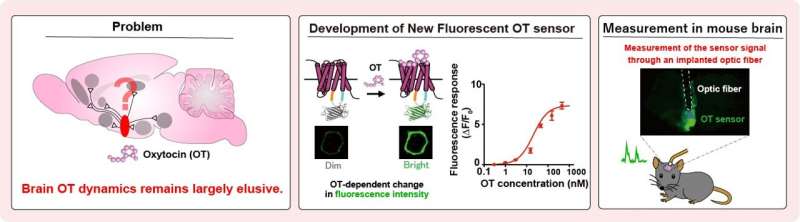

In a new study published in Nature Methods, researchers led by Osaka University reported their development of a novel fluorescent sensor for the detection of OT in living animals. OT plays an important role in a variety of physiological processes, including emotion, appetite, childbirth, and aging.

Impairment of OT signaling is thought to be associated with neurological disorders such as autism and schizophrenia, and a better understanding of OT dynamics in the brain may provide insight into these disorders and contribute to potential avenues of treatment. Previous methods to detect and monitor OT have been limited in their ability to accurately reflect dynamic changes in extracellular OT levels over time. Thus, the Osaka University-led research team sought to create an efficient tool to visualize OT release in the brain.

“Using the oxytocin receptor from the medaka fish as a scaffold, we engineered a highly specific, ultrasensitive green fluorescent OT sensor called MTRIAOT,” says lead author of the study, Daisuke Ino. “Binding of extracellular OT leads to an increase in fluorescence intensity of MTRIAOT, allowing us to monitor extracellular OT levels in real time.”

The research team performed cell culture analyses to examine the performance of MTRIAOT. Subsequent application of MTRIAOT in the brains of living animals allowed for the successful measurement of OT dynamics using fluorescence recording techniques.

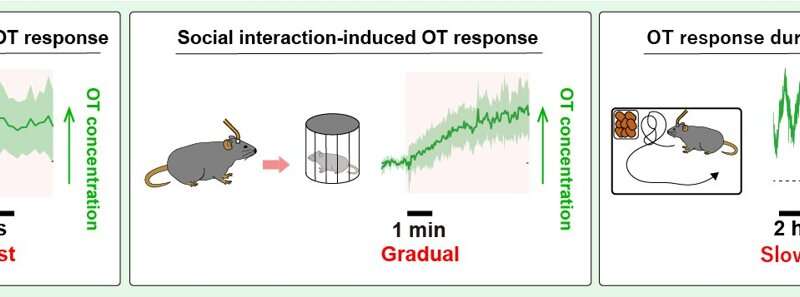

“We examined the effects of potential factors that may affect OT dynamics, including social interaction, anesthesia, feeding, and aging,” says Ino.

The research team’s analyses revealed variability in OT dynamics in the brain that was dependent on the behavioral and physical conditions of the animals. Interactions with other animals, exposure to anesthesia, food deprivation, and aging all corresponded with specific patterns of brain OT levels.

Source: Read Full Article